Refutational Writing

|

Stage 1: Introduce the Writing Prompt

Each refutational writing prompt provides students with a particular misconception to refute. It then outlines all the information a student will need in order to write, such as the topic, the audience, the purpose, the form of the text, and reminders or ‘must-haves’. The reminders or ‘must-haves’ are designed to focus the writer’s attention on important components of a quality refutational text that novices often forget or do not provide enough attention to in their writing. The prompt then concludes with information about the steps of the writing process that the student should follow (e.g., conducting research, creating an outline, producing a rough draft, peer review, editing, and publication). It also provides a space for the teacher to assign a due date for each step of the process.

Each refutational writing prompt provides students with a particular misconception to refute. It then outlines all the information a student will need in order to write, such as the topic, the audience, the purpose, the form of the text, and reminders or ‘must-haves’. The reminders or ‘must-haves’ are designed to focus the writer’s attention on important components of a quality refutational text that novices often forget or do not provide enough attention to in their writing. The prompt then concludes with information about the steps of the writing process that the student should follow (e.g., conducting research, creating an outline, producing a rough draft, peer review, editing, and publication). It also provides a space for the teacher to assign a due date for each step of the process.

Stage 2: The literature review

Students conduct a literature review to gather the information they need to craft a refutational text. As part of the process, they must narrow or broaden the inquiry as appropriate, gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources, use advanced searches effectively, and assess the usefulness of each source. Students must also determine the central ideas or conclusions of a text, trace the text's explanation or depiction of the topic, provide an accurate summary of it, and cite specific textual evidence to support their analysis of it. This stage is important because students need to be able to read and comprehend science texts independently and proficiently by time they graduate from high school.

Students conduct a literature review to gather the information they need to craft a refutational text. As part of the process, they must narrow or broaden the inquiry as appropriate, gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources, use advanced searches effectively, and assess the usefulness of each source. Students must also determine the central ideas or conclusions of a text, trace the text's explanation or depiction of the topic, provide an accurate summary of it, and cite specific textual evidence to support their analysis of it. This stage is important because students need to be able to read and comprehend science texts independently and proficiently by time they graduate from high school.

Stage 3: Pre-Write

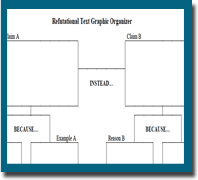

Students generate an outline for their refutational text. As part of this process, students must determine how to introduce claims, create an organization that establishes clear relationships among the claims, reasons, and evidence, develop each claim fairly, and what information will be used to support or challenge a claim in a discipline-appropriate form and in a manner that anticipates the audience's knowledge level and concerns.

Students generate an outline for their refutational text. As part of this process, students must determine how to introduce claims, create an organization that establishes clear relationships among the claims, reasons, and evidence, develop each claim fairly, and what information will be used to support or challenge a claim in a discipline-appropriate form and in a manner that anticipates the audience's knowledge level and concerns.

Stage 4: Initial Draft

Students produce an initial draft of the refutational text. As part of the process, the students must introduce the topic and organize information to make important connections and distinctions, include proper formatting (e.g., headings) and add graphics (e.g., figures, tables) as needed to foster comprehension. Students must support or challenge claims with well-chosen, relevant, and sufficient facts, concrete details, quotations, and other information that they gather during the literature review. The essays should include varied transitions and sentence structures to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships among ideas and concepts, and a concluding statement or section that follows from or supports the argument presented. The students should also use words, phrases, and clauses to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claims, claims and reasons, and between reasons and evidence. Finally, the students should establish and maintain a formal style and objective tone while attending to the norms and conventions in science.

Students produce an initial draft of the refutational text. As part of the process, the students must introduce the topic and organize information to make important connections and distinctions, include proper formatting (e.g., headings) and add graphics (e.g., figures, tables) as needed to foster comprehension. Students must support or challenge claims with well-chosen, relevant, and sufficient facts, concrete details, quotations, and other information that they gather during the literature review. The essays should include varied transitions and sentence structures to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships among ideas and concepts, and a concluding statement or section that follows from or supports the argument presented. The students should also use words, phrases, and clauses to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claims, claims and reasons, and between reasons and evidence. Finally, the students should establish and maintain a formal style and objective tone while attending to the norms and conventions in science.

|

Stage 5: Double blind peer-review

Groups of students review several essays in order to ensure quality and to provide their classmates with the feedback they need in order to improve. This stage of the model helps students learn how to evaluate information in science. It also helps students develop their ability to read and critique refutational arguments. |

Stage 6: Revise and publish

Students use the feedback from the peer review to revise their refutational essays. The essays are then submitted to the teacher for a final evaluation. This stage of the model is designed to help students learn how to strengthen writing as needed by revising and rewriting based on feedback. It also gives students an opportunity to use technology, including the Internet, to produce, publish, and update a writing product and take advantage of technology's capacity to promote and support the production and distribution a scientific text.

Students use the feedback from the peer review to revise their refutational essays. The essays are then submitted to the teacher for a final evaluation. This stage of the model is designed to help students learn how to strengthen writing as needed by revising and rewriting based on feedback. It also gives students an opportunity to use technology, including the Internet, to produce, publish, and update a writing product and take advantage of technology's capacity to promote and support the production and distribution a scientific text.

Learn more

To learn more about the Refutational Writing Instructional Model, see:

Dlugokienski, A. and Sampson, V. (2008). Learning to write and writing to learn in science: Refutational texts and analytical rubrics. The Science Scope, 32(3), 14-19.

Sampson, V., and Schleigh, S. (2012). Scientific Argumentation in Biology: 30 classroom activities. Arlington, VA: NSTA Press.

Sampson, V., and Schleigh, S. (2012). Scientific Argumentation in Biology: 30 classroom activities. Arlington, VA: NSTA Press.